The one way mathematics does find itself into other subjects during K-12 is through formulas. You can think of these as recipes with numbers. Take something as basic as Newton’s second law which most first year students know to read F=ma. Many students in fact think this is what mechanics is; a set of formulae to be memorized.

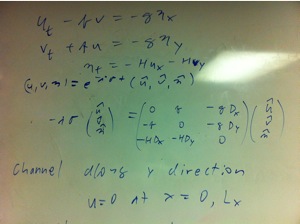

Of course F=ma is not Newton’s second law, which actually says that the rate of change of the linear momentum vector is given by the net force vector, something that needs to be expressed in the language of calculus and differential equations to get right. Still let’s say we did take the formula F=ma at face value. What does it say?

It does give a recipe for calculating F, but only assuming you know, or can measure m and a. It also tells you something about the units of F, assuming again you know the units of m and a. Finally, it implies you accept certain ideas about physics, the notion of mass being associated with a single point, for example. That’s a fair amount of baggae for something that looks as simple as F=ma.

That’s, in fact, the great attraction of formulas; they pack a great deal of information into a tidy package. In fact this is the point of much of the crazy looking notation mathematics uses. We wish to express the most information in the smallest, most unambiguous package. Sometimes this leads to confusion, and often to successfully apply mathematics one needs to go back and forth between the tidy world of formulae and the messy, subjective world of language.

Formulae and their meaning