Sources:

We consider complex functions of a real variable. Such a function is periodic if there is a period $T$ such that for all $t$, \[ f(t+T) = f(t). \]

Now we want to introduce almost-periodic functions. A number $\tau$ is an $\epsilon$-period for a function $f$ if, for all $t$, \[ |f(t)-f(t+\tau)| \le \epsilon. \] A function is then almost periodic if, for each positive $\epsilon$ there is a real number $\ell$ such that each real interval of length $\ell$ contains an $\epsilon$-period. (This is Bohr's definition, there are number of different flavors. Corduneanu denotes this one by $AP(\re,\cx)$.) A subset $\cP$ of $\re$ is relatively dense if there is a real number $\ell$ such that that each real interval of length $\ell$ contains an element of $\cP$. So an almost periodic function has a relatively dense set of $\epsilon$ periods.

Using this definition it is not hard to show that the almost-periodic functions form a algebra. Since $e^{it\theta}$ is periodic when $\theta\in\re$, it follows that if $\seq a1n$ are complex and $\seq\theta1n$ are real, the function \[ f(t) = \sum_{r=1}^n a_r e^{it\theta_r} \] is almost periodic.

We apply this to $U(t)$. Certainly the entries of $U(t)$ are almost periodic. Suppose $U_0=U(t_0)$. Then \[ \tr((U(t)-U_0)^* (U(t)-U_0)) = \tr(2I- U(t)^*U_0-U_0^*U(t)) \] is an almost-periodic function that is zero at $t_0$. Hence for each positive $\epsilon$ there is a relatively dense set $\cP$ such that $\|U(\tau)-U_0\|\le\epsilon$ for all $\tau$ in $\cP$. One consequence of this is that every graph is "approximately periodic".

It is a theorem due to Bohr that a function is almost periodic if and only if it is the uniform limit of finite complex linear combinations of exponentials $e^{it\theta}$ (with $\theta$ real). If $f(t) = \sum a_re^{it\theta_r}$ we can define \[ \|f\|_1 := \sum |a_r|. \] This is a norm on the space of finite linear combinations of exponentials, and the completion of this space with respect to this norm is a proper subspace of the space of almost-periodic functions. Corduneanu denotes this class by $AP_1(\re,\cx)$.

Since the idempotents $E_r$ are positive semidefinite, we have \[ |(E_r)_{u,v}| \le (E_r)_{u,u}^{1/2}\,(E_r)_{v,v}^{1/2}. \] So \[ \sum_r |(E_r)_{u,v}| \le \sum_r (E_r)_{u,u}^{1/2}\,(E_r)_{v,v}^{1/2} \le \left(\sum_r (E_r)_{u,u}\right)^{1/2} \left(\sum_r (E_r)_{v,v}\right)^{1/2} =1. \] This shows that $\|U(t)_{u,v}\| \le 1$, and that the entries of $U(t)$ belong to $AP_1(\re,\cx)$.

The theory seems to extend as we would expect. So if $M(t)=\frac{1}{n}J$, then there is a relatively dense set of times such that $M(t)$ is within $\epsilon$ of $\frac1{n}J$. Note that in the known cases where we have uniform mixing, the graphs are periodic.

If $\seq f1k$ are almost periodic, then the vector-valued function \[ f(t) = \pmat{f_1(t)\\\ \vdots\\ f_k(t)} \] is almost periodic.

Assume \[ f(t) = \sum_{r=1}^n a_r e^{it\theta_r}. \] Then \[ f^{(k)}(t) = \sum_{r=1}^n (i\theta_r)^k a_r e^{it\theta_r}. \] Assume we have exactly $m$ distinct eigenvalues and let $M$ be the Vandermonde matrix with $M_{r,a}=(i\theta_r)^{a-1}$. Since $M$ is invertible, we see that if $f^{(k)}(t)=0$ for $k=0,\ldots,m-1$, then $f$ is the zero function.

Assume \[ g(t) =\frac12(f(t)+\comp{f(t)}),\quad h(t) =\frac1{2i}(f(t)-\comp{f(t)}), \] so $g$ and $h$ are the real and imaginary parts of $f$. Then $g$ and $h$ are almost periodic, as is \[ g_\delta(t) := g(t)g(t+\delta). \] If $g_\delta\lt0$ for some value of $t$, then it is negative infinitely often; since $g_\delta$ is continuous it follows that there are infinitely many intervals of length $\Delta$ that contain a zero of $g$. A similar claim follows for $h$. For bipartite graphs the entries of $U(t)$ are either real or purely imaginary. And $U(t)_{u,v}$ is an even or odd functions, according as the distance between $u$ and $v$ is even or odd. So we get infinitely many zeros for $U(t)_{u,v}$ when $u$ and $v$ are at odd distance in a bipartite graph. [***I need to check this. And for $P_4$ we get infinitely many zeros for $U(t)_{0,2}$.***]

Suppose $u$ and $v$ are not adjacent and $g(t)$ is the real part of $U(t)_{u,v}$. Then near zero $U(t)\approx I+tA$, in fact if $u$ and $v$ are at distance $d$ then 0 has multiplicity at least $d$ as a zero of $g$. Our argument with $g_\delta$ only allows us to argue that if $g$ has a simple zero, it has infinitely many.

Suppose \[ f(t) = \sum_r a_r e^{it\theta_r} \] If the eigenvalues $\theta_r$ are rational then $f(t)$ is periodic. Otherwise the set of eigenvalues has a basis over the rationals, say $\seq\theta1d$. By Kronecker's theorem the points \[ (e^{im\theta_1},\ldots,e^{im\theta_d}),\qquad m\in\ints \] are dense in the $d$-dimensional torus. If $\varphi$ is a rational linear combination of basis elements, there are integers $c$ and $\seq c1k$ \[ c\varphi = \sum_{r=1}^k c_r \theta_r \] Suppose $m$ is chosen so that the numbers $m \theta_r$ for $r=1,\ldots,k$ are within $\epsilon$ of an integer multiple of $2c\pi$, then $m\varphi$ is close to an integer multiple of $2\pi$. It follows that, for each positive $\epsilon$ there is a positive integer $m$ such that $\|U(m)-I\| \le\epsilon$.

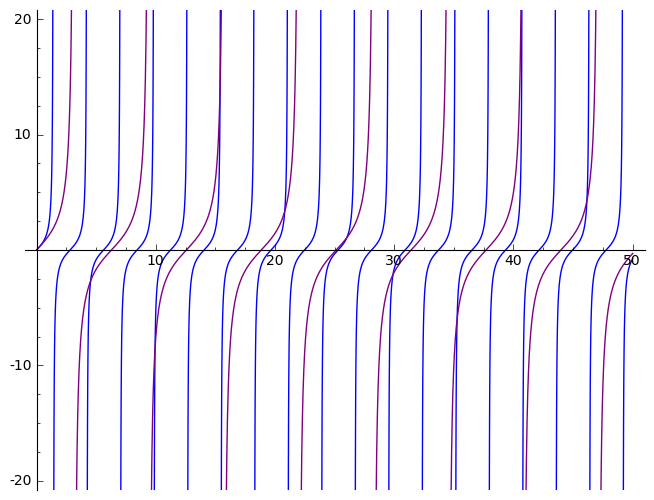

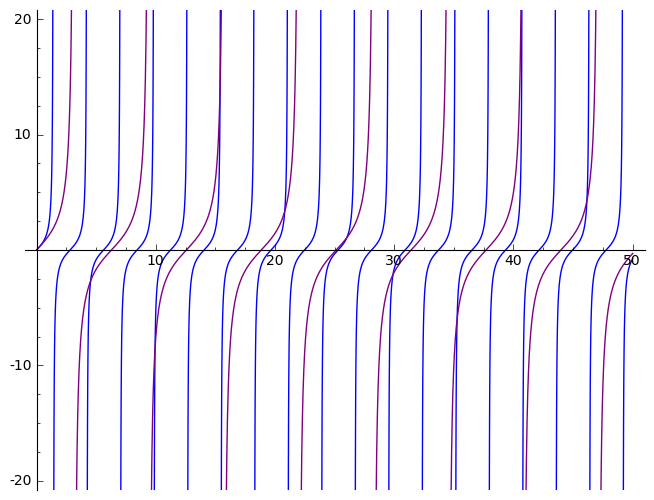

We work on the path $P_4$ with vertex set $\{0,1,2,3\}$. Then \begin{align*} U(t)_{0,3} &= \frac{1}{5+\sqrt{5}} \exp\biggl(it\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\biggr) + \frac{1}{5-\sqrt{5}} \exp\biggl(it\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\biggr) - \frac{1}{5+\sqrt{5}} \exp\biggl(it\frac{-1-\sqrt{5}}{2}\biggr) -\frac{1}{5-\sqrt{5}} \exp\biggl(it\frac{-1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\biggr)\\ &= \frac{2i}{5+\sqrt{5}}\sin\biggl(\frac{(1+\sqrt{5})t}{2}\biggr) +\frac{2i}{5-\sqrt{5}}\sin\biggl(\frac{(1-\sqrt{5})t}{2}\biggr)\\ &= i\sin(t/2)\cos(\sqrt{5}t/2) -\frac{i\sqrt{5}}{5}\cos(t/2)\sin(\sqrt{5}t/2). \end{align*} Hence $U(t)_{0,3}=0$ if and only if \[ \tan(\sqrt{5}t/2) = \sqrt{5}\tan(t/2). \] If $m\in\ints$ then $\cot(t/2)$ is strictly decreasing on the interval $[m\pi/\sqrt{5},(m+1)\pi/\sqrt{5}]$ of the reals with maximum value $\infty$ and minimum value $-\infty$, each such interval From the plot below, it seems that each of length $2\pi/\sqrt{5}$ contains at least one zero, and most two.

Here are the two tangent functions plotted in the same place,

with $\sqrt{5}\tan(t/2)$ in blue.

To Do: